- Home

- Travel Writing Craft Resources

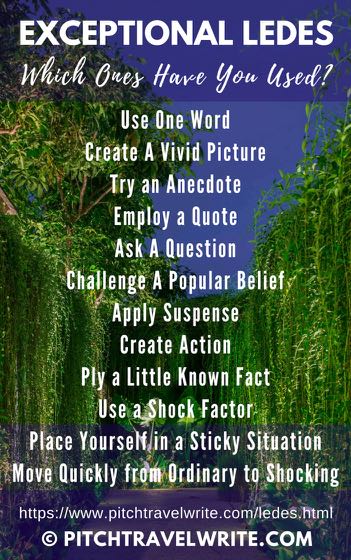

- Writing Exceptional Ledes

WRITING EXCEPTIONAL LEDES

And Why It Matters

To Travel Writers

By Roy Stevenson

Do you want to grab your reader’s attention immediately? Most of us do. To accomplish this, your opening sentence needs to be captivating.

In the writing trade your opening sentence is called a “lede”. It’s one of the most crucial and underutilized travel writing techniques. But it can make such a difference to the quality of your piece!

If you want to engage your readers right from the start, the lede is your single most important tool. Also known as a “hook” (and sometimes spelled “lead”) it activates your audience to keep reading and to see where you’re going with your story.

You can use many different types of ledes. And all of them will command your readers’ attention if done well.

Here

are 12 of my favorites, placed in ascending order of difficulty.

Unless otherwise noted, examples of ledes are from my own travel

stories.

One Word Ledes

Amazing! One (or two) dramatic words can snag your reader’s attention. If you see an opportunity to use one word that best encapsulates your story or travel experience, use it. But do make sure you continue on to elaborate on the key word or your story will lack credibility and punch. It will fizzle out.

Here’s a two-word lede that I used in a story about the Roman Gold Mines in Wales:

“Welsh gold. This rare and soft lustrous gold is the most expensive gold in the world. It fetches up to $4500 per ounce, or three times what standard gold sells for in the London market.”

Create a Vivid Picture of the Place Lede

For dramatic destinations, use a sentence of short and simple words to create a vivid picture in our minds. These ledes encourage imagery and help us imagine the place.

Vivid descriptions set the stage for the rest of the story. Here are three of my descriptive ledes:

“Pedaling leisurely along the towpath beside the Burgundy Canal, I glide past neat rows of old oaks, maples, and poplars that form a tall, shady green cathedral along the flanks of the shallow canal.”

“The immaculate little town of Baden-Baden, tucked away in the foothills of S.W. Germany’s Black Forest, is a luxurious cross between Monte Carlo, Paris, a spa, and an English park.”

“Looking out over a green expanse of gently rolling farmland, dotted with piles of newly mowed hay, it’s hard to believe that the most famous battle in English history was fought here.”

The Anecdote Lede

A short, true story (usually written in italics) about an aspect of the destination gets our attention smartly.

In the National Geographic story “Uncommon Kingdom”, Archer Mayer begins his story:

“There’s a habit in some of the more remote sections of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. When you drive up to a person’s out-of-the-way home, you honk your horn and wait before exiting your vehicle. So the dogs can gauge your intentions. It’s a form of politesse. It’s also not too dumb an idea.”

This lede lets you immediately picture yourself in the car - and wonder about a place where you need to wait for the dogs to figure out your intentions.

The Quote

An interesting quote can introduce your destination storyline. Make sure your quotation is appropriate for the destination you’re writing about. If it’s even a little off base, it will sound nonsensical.

“Prague never lets you go. . . this dear little mother has sharp claws”. So wrote Franz Kafka, the Czech Republic’s favorite writing son. And he was right. Within a few hours of arriving in Prague, you’ll realize why this ancient Czech city is called the jewel in the crown of central Europe.

“A York! A York!” yells the York’s banner bearer, as he works the excited crowd up into a lather.

Leading with the right quote puts your readers into the story immediately.

The Ask-A-Question Lede

Your question should provoke and engage your audience. Make it controversial versus banal. You might have noticed I started this article with a question. It led you into the main subject of the story.

Recently Bill Nye began a National Geographic article with the question:

“Do you know the current phase of the moon?”

It’s a simple question but one that made me stop, think about it, and then wonder why it was important. All done in a split second, I kept reading to find out more.

That’s what you want your readers to do with your ask-a-question ledes – stop, think, and then keep reading.

The Little-Known-Fact Lede

Readers love to see facts and figures about a destination if presented in an interesting way:

“There’s a good reason why 3 million people visit Heidelberg every year.”

“The medieval stone city of Edinburgh boasts a staggering 700 pubs for its population of just under 500,000, the highest concentration of pubs in Great Britain.”

“Tucked away amidst the rolling green hills of Southwest England’s Somerset County, the small mystical town of Glastonbury has more myth and legend attached to it than any other place in England—including Stonehenge.”

Action Ledes

The action lede places yourself in a dramatic scene, then reverts back to the beginning of your story.

“The loud, rhythmic sounds of people chanting and drumming and the sight of hundreds of others dressed in multi-colored batik sarongs and swirling skirts are overwhelming. Sensory overload sets in from the bright sunshine, suffocating heat and humidity, and sweet perfumed smell of flowers and incense wafting across the potholed, asphalt road.”

Suspense Ledes

Can you think of something surprising that you can hint at early in your story, and answer or elaborate on later? This is often done in soft news stories, where the surprise point comes in the first paragraph and the news comes later.

It can also be used in travel stories, like this one about a bespoke umbrella-maker in Italy:

“Just like you, I own seven umbrellas. They are all broken-blown inside out by the wind, torn by my cat, the metal ribs bent at awkward angles or cutting right through the fabric. I used to own 10 but three were left in restaurants, on the subway, or in somebody’s car. I buy a new one almost every time it rains. About 33 million umbrellas are sold each year in the United States, a figure I’m confident comes from the fact that we lose or break our little fold-up portables all the time. In London, tens of thousands of umbrellas are left on the Underground every year.” (National Geographic Traveler, April/May 2018, Article written by Ann Hood)

The surprise is with the number of umbrellas we buy and lose. We want to know what comes next. Maybe we’ll learn how to stop buying and losing all those umbrellas!

Challenge a Popular Belief or Stereotype

Make a controversial cultural statement and then explain it or destroy it.

“In the not too distant past, I bought into the idea that the French were the most obnoxious people on the face of the earth. But then . . .”

The Shock Factor Lede

Revealing a shocking, startling, or interesting fact about a place is an effective way to command your reader’s attention right from the start. It begs for more details and context.

Your shocking fact(s) can be positive or negative, and your goal is to make your reader curious.

“In 1786, 34-year old Joseph Golding was cutting a garden seat into the side of a cliff overlooking the famous coastal town of Hastings, England when his pick broke through the rock. He gazed in awe down into a vast cavern.”

“Every year hundreds of thousands of Belgian and European beer lovers from neighboring countries like Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Luxembourg travel for hours to the St. Sixtus Monastery in the tiny Belgian town of Westvleteren in West Flanders.”

“On June 6, 1944, 150,000 American, Canadian and British troops landed in rough seas along a sixty-mile series of flat sandy beaches on the French coast at Normandy.”

Shock Factor Lede #2:

Place Yourself in a Precarious Situation

Likewise, placing yourself in a shocking or tense situation grabs our attention and holds it—we want to see how you got out of the sticky situation.

In this National Geographic Traveler article named “Not So Easy Rider”, writer Andrew McCarthy begins:

“The scraggly tree beside my fallen motorcycle provided no relief from the African downpour. The rain sounded like machine-gun fire as it pelted the plant’s few tattered fronds. I looked back over the sandy dirt lane I’d been riding until a deep rut had thrown me to the ground. The potholed road had turned into riotous little pools of water. There were no buildings in sight, no other signs of life. I bent over to inspect a deep scrape on my knee. What had I been thinking?”

Another Shock Factor Lede:

From Ordinary to Shocking

Going quickly from an ordinary moment to a shocking one gets our attention.

Here’s an example from an article in National Geographic Traveler by Neil King called “Obsessions Swimming”:

“When my first daughter was three weeks old, I dunked her into the Mediterranean an hour’s drive outside Rome. She squealed. When she was two, she would beg to go out stomping through the rain puddles in Brussels. I obliged. When she was seven, she pleaded for me to throw her into the frigid Roaring Fork River, in the Rockies outside Aspen. I did so, with glee, and dove in myself.”

General Advice about Ledes

If you have difficulty finding focus for your lede ...

. . . ask yourself what it is about your destination or experience that resonates with you. Can you distill this thought or this feeling down into one word, one sentence or an anecdote?

The first thing you should ask when writing your travel story is, “What is going to be my lede?” Find your focus before you proceed.

Here's a lede identification exercise to try

Thumb through several travel stories in magazines and books, and identify each lede sentence or paragraph. This is fun!

You’ll become proficient at identifying ledes very quickly. And this will quickly transfer to your writing as you gather ideas and insights from other professionals.

Things to Avoid

Don't make in sound like an advertorial.

How many stories have you read that begin like travel advertorial, similar to these?

As soon as you set foot in xxx you’ll realize it’s like no place else in the world. A melting pot of cultures ...

In this piece of paradise, xxx is pure luxury and refinement blended with pure moments of bliss.

Perfect days don’t have to be complicated. A late breakfast on a

sunlit terrace, a long swim in an azure sea, lunch beneath a twist of

vines - picture a fresh, bright salad and perhaps a glass or two of

wine.

You lose your reader immediately with these kinds of starts. Their eyes

glaze over and they stop reading. A good lede saves you from going

down this misguided path.

Never start your story with “I”. Never.

This is a common way beginner travel writers kick off their stories. It seems so easy but it’s actually lazy. Using “I” means you can’t be bothered crafting an interesting or clever lede, and it screams “beginner” to magazine editors. You don’t want your story to read like your sixth grade vacation report.

It’s not difficult to correct this error. Instead of saying “I’m in London walking along the banks of the Thames, enjoying seeing the Londoners walking briskly to work”, say “Walking along the banks of the Thames, I enjoy seeing the Londoners walking briskly to work.”

There's more you can do to improve this lede, but removing "I" at the beginning is a good start.

Don’t use clichés.

Don’t use them in your ledes or in your stories.

Avoid using passive tense in your ledes (and in your stories).

Passive words make your stories flop around like a fish out of water, gasping for air. Passive tense is using any versions of the verb “to be” – you can learn more is a separate story I wrote about readability.)

Hone Your Craft

This article has 12 of my favorite travel ledes, but there are plenty more. Travel writers need to be proficient with several types of ledes. Having a variety of ledes in your toolbox helps you vary your openings and focus your articles.

If you want your readers to finish your stories, you have to be fast off the mark. Get better at writing attention-grabbing sentences and your travel stories will be off to a moving start.

With dynamic and active words, you’ll create a satisfying and emotional experience that will engage your reader. If you can do this in your lede sentence, you’ll crush it!

Do you struggle to craft an engaging story,

and wonder how to get past this barrier?

There are many tools and techniques you can learn. And they're not difficult!

If

you’re prepared to work on your writing style and make improvements,

you’ll get your stories published in highly respected, paying

publications.

The Art and Craft of Travel Writing is a handy reference with tips and techniques to help you.

Related articles that will interest you:

Roy Stevenson is a professional travel writer and the author of www.PitchTravelWrite.com. Over the past ten years, he’s had more than 1000 articles published in 200 magazines, trade and specialty journals, in-flights, on-boards, blogs and websites and has traveled on assignment around the U.S. and to dozens of international destinations.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS POST, GET UPDATES. IT'S FREE.